M Squad: Lee Marvin Gets His Man (and Woman)

January 26, 2011 § 7 Comments

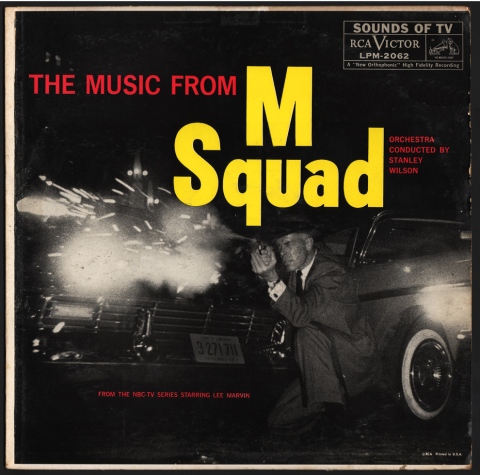

This is a soundtrack album from the late-’50s TV series “M Squad.” The noir-tinged police drama, which ran from 1957 to 1960 on NBC, featured Lee Marvin as Lt. Frank Ballinger, a member of an elite plainclothes division of the Chicago force dedicated to battling gangsters, corruption and violent crime in the Windy City. Marvin had been appearing in films since 1951, but “M Squad” made him a star. The show also featured great bebop jazz by top-flight composers such as Count Basie and Benny Carter as well as early appearances by people like Angie Dickinson, Burt Reynolds and Don Rickles. The full set of 117 episodes was reissued a few years ago (although some had to be sourced from the public as original copies were hard to come by, so the quality apparently varies wildly), and the reviewer at Amazon described the series as “tough and no-nonsense:”

“Filmed in Chicago, ‘M Squad’ is my kind of cop show, with an authentic sense of place, a driving, brassy jazz score, shady characters with names like Johnny East Side, a captain feeling the heat from ‘downtown’ (‘They want the killer; they want him real bad’), and hard-boiled dialogue (Cop: ‘Where’d you get that money?”‘ Suspect: ‘From the guy who had it’).”

I wasn’t familiar with the show, but, like anyone who was raised on and loved the better-known “Dragnet,” I was immediately captivated by the imagery and dialogue. It’s hard to beat hearing a 1950s cop utter lines like – as Marvin summed up at the end of one episode – “The people of Chicago, they look pretty good to me right now. The town looked clean, honest and innocent.”

Lee Marvin, Benny Carter and Stanley Wilson on the set of "M Squad," Universal Studios, c. 1959. (Photo courtesy Benny Carter)

Dvdtalk.com cites the show’s “be-bop, jazzy, brutal hipster sensibility…jazzed up with…the blindingly cool music cues of legend Benny Carter (who eventually scores most of the third season episodes),” and it was Carter who initially intrigued me when I sat down to write about the album. Born in 1907, the multi-instrumentalist, composer, arranger and bandleader was a major figure in jazz for a remarkable eight decades, finally passing away in 2003. But as I started reading more about Lee Marvin, I became increasingly fascinated with his story. Most people are of course familiar with him and at least some of his films, but many wouldn’t know that he saw intense combat as a Marine scout sniper in the South Pacific during WWII. Participating in 21 island landings, he was eventually wounded and almost killed in the Battle of Saipan, which saw the largest Japanese suicidal banzai charge of the war and in which most of his unit was wiped out (Marvin was one of three survivors). After 13 months of hospitalization he returned to New York in 1945. There – as legend has it, in any case – he fell into acting when, working as a plumber’s assistant at a local community theater upstate, he was asked to fill in for a sick actor at a rehearsal. He discovered he loved it, and soon left to join a theater group in North Carolina before moving to New York City to study and take roles off Broadway. In 1950 he relocated to Hollywood, and by 1953 he was playing opposite Marlon Brando in The Wild One.

1953 also saw Marvin portray what was probably his first really memorable villain, in Fritz Lang’s classic film noir The Big Heat. Most commentators say this is where the actor first really came into his own as a uniquely menacing screen presence, and Lang himself called his performance “more than just another role; it became his calling card.” Playing a gangster, Marvin (“in a sudden outburst that set a new bar for screen violence and typed him as a volatile, dangerous bad guy for years to come,” according to Rob Nixon on tcm.com) throws a pot of boiling coffee in his girlfriend’s face, disfiguring her. As the film writer Patrick McGilligan points out, though, “It is not the spectacle of scalded, ruined beauty, but the evil of Marvin’s face and lips, glistening and quivering in Lang’s close-up of him, that gives realistic horror to the scene.”

Marvin went on to forge a career out of his ability to inhabit this sort of character, but the irony is that his time in battle had actually hardened him in some ways against Hollywood depictions of violence. As Ian Terry writes, “His experiences during war clouded the rest of his life. Marvin’s later career as actor would define him as an on-screen tough guy, yet he was an outspoken opponent against screen violence. Having witnessed death first-hand (he tellingly described his own actions as ‘murder’), he understood the nature of aggression better than most, voicing little tolerance for the fist-fights seen in John Wayne style of western.”

Marvin himself explained it this way: “Only in the sense that if the violence in a film is theatrically realistic, it’s more of a deterrent to the audience committing violence themselves. Better on the screen than off. If you make it realistic enough, it becomes so revolting that no viewer would want any part of it. But most violence on the screen looks so easy and so harmless that it’s like an invitation to try it. I say make it so brutal that a man thinks twice before he does anything like that.” As Brynn White writes, “At the age of 21 Marvin knew enough of humankind’s cruelty; he knew its horrors as well as its seductive draw. He knew what real violence looked like, and this knowledge seemed to haunt his every move.”

The guy was – apart from being by almost all accounts a strikingly agile and intuitive actor – a unique character: clearly his own man, one who’d seen about as much as anyone can, had come back from it and just sort of didn’t care…and there’s nothing cooler than that. Even his attitude towards death toed that line: “I don’t want any more than I’ve got coming to me, and I don’t understand those who do. Like, why would anyone want to undergo a heart transplant? A person would have to have led a pretty empty life to be that frightened of dying. How would you like to be walking around with a 17-year-old broad’s heart in your chest, just to live a few years longer?… Jesus, give me my span of years and knock me down when it’s all over. You’ve got to make room for the other guy. I know that when my ashes are blown away or they stuff me in a sewer, it’s not going to hurt. I’ve had the simple pleasure of being present when the sun was shining and the rain was falling. I’ve had mine, and nobody can take it away from me.”

What’s more, the British director John Boorman, who directed Marvin in two movies, including Point Blank, observed that just about everyone tended to like him, especially film crews, stunt men and the like; and Jeff Bridges, who worked with Marvin in the ’70s, described him as an unusually kind and giving actor. He certainly seems to have been incredibly down-to-earth. Marvin on himself: “I can’t stand myself. If I could, I’d play the same guy in all my roles. I don’t even like my own company; I’ve got nothing new to tell myself. Nor do I like the company of other actors; if I don’t like myself, how could I like them? Since I can’t go out in public as much as I used to, I do most of my socializing with the working stiffs on the set during a movie – the stunt men, the gaffers, the propmen. These behind-the-scenes guys keep me straight. They’re working men; from their attitudes and the discussions I have with them, I get a sense of what I must do with my current role or my next one. It keeps me on their level – the level of the public. So I shoot the bull with them, hoist a few drinks, share some laughs instead of going into my dressing room and picking up the phone and calling Paris while I drink the chilled champagne. It keeps me from becoming a ‘star.'”

John Boorman on Lee Marvin; includes some great film footage

And all that from a man who was a a direct descendant of no less than Thomas Jefferson and twice a descendant of a male line of relatives of George Washington (Marvin’s mother, for one, was descended from George Washington’s brother Augustine). He was even a second cousin twice removed of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, for whom he was named. But after all of that, the element that perhaps caught my attention as much as anything was the fact that later in life Marvin tracked down and married his hometown girlfriend, Pamela Feeley, whom he had last dated 21 years earlier. That had been in 1949, soon after he returned from the war. The two had met in Woodstock when she was 15 and he was 21 (she saw him at the local swimming hole and apparently “fell instantly in love”); at 18 she aborted their child in a backstreet operation. Soon afterward, Marvin “left [her] in the lurch,” giving up his idea to open a business to embark on his acting career. Then, in 1970, with eight children and four marriages between them, they married and lived happily until Marvin’s death in 1987.

For some reason stories like that always appeal to me, and when I saw that Marvin had married an early flame later in life, I felt like it would be an interesting angle to take for this post. I wasn’t sure, though – until I was removing the record from the sleeve and out came a folded-up section of a 1997 newspaper (I had no idea it was in there, this being another record I hadn’t yet played) with a big article on a book Marvin’s widow had just published on their amazing story. If that wasn’t a sign, I don’t know what would be.

As she tells it, though, the chain of events sounds pretty incredible. It seems that Marvin would return to town periodically and pop in for coffee. “This happened about four or five times,” Pamela recounts, “and then I took a trip to California and he picked me up for dinner. He took me out to his house in Malibu and showed me his Oscar and all his memorabilia. We went for a walk on the beach.” In another interview, with A.J. Flick on classicmovies.org, she fills in some of the story: “‘We didn’t even hold hands….Nothing. He was just telling me everything he’d done, showing me everything.’ Showing off? ‘In such a nice, wonderful way. So proudly,’ she said, nodding.”

Pamela felt Marvin might be still in love with her (by this point he had been divorced for a few years from his first wife of almost 16 years; she was divorced too – for a third time), but the next time he passed through Woodstock, later that year, he was on his way to New York to do publicity for the movie “Monte Walsh” and conducting an affair with his co-star Jeanne Moreau. “I said to myself: Oh God, Pam, forget it. Jeanne Moreau. Who could compete with her?”

After he was done in New York, though, Marvin returned to Woodstock, called Pamela and told her not to “go anywhere tonight. You be home.” She packed the kids off to her mother’s and baked an apple pie, so she must have been anticipating something – though it was probably more along the lines of a nice visit. Instead, Marvin pulled up in a limo, strolled in with a big suitcase and said, “OK, let’s go. I’ve come to get you. You know that, don’t you? We’re getting married.” Hard to believe, but that’s what seems to have happened. To top it off, Frank Sinatra sent his private jet and the couple flew to Las Vegas to tie the knot. “He was at the height of his career and I was struggling along with four kids. And here he comes, my knight on his white charger. It was wonderful. Cinderella in a way.”

As the classicmovies.org interview rounds out the picture: “Lee took pains to keep her in his life. He wasn’t about to lose her again. ‘He was really good about how he introduced me to the whole world,’ she said. First, he shuttered Pamela, her children and his children away in Malibu without any outsiders. Then he introduced her to his friends. Then the Hollywood scene. Then he brought her to TV appearances. ‘He really did it very nicely, slowly,’ Pamela said.”

Marvin wasn’t always easy to live with – in many ways – but she emphasizes that he was “so good to me and my children. We brought up two of our grandchildren from when they were very small. He didn’t want to become a parent again at his age but he did it because it was the right thing to do.”

For her part, John Boorman, who became a close friend of both Lee and Pamela, says that Pamela was “so warm and motherly, and adored Lee. She gave Lee a sense of home, a place where he could be himself. He became much more relaxed, much funnier.” There was, as he puts it, “a wonderful ease between them.” Boorman encouraged her to write her memoir of the relationship, describing her as “terribly heartbroken” when Lee died at the relatively young age of 63, possibly aided by some mistakes doctors had made in treating him. “Ten years writing the book was a way of keeping him alive. When she finished it, I think it was quite traumatic for her.”

I can’t find very much current information on Pamela Marvin, but it looks like she now resides again in Woodstock, where she is active with the local film festival. Coincidentally, and to return to the “M Squad” album, Benny Carter also married someone from his past. In 1979 he wed his fifth wife, Hilma Ollila Arons, whom he had first met in 1940 when she went to the Savoy Ballroom to hear his band. I don’t know anything about what transpired in that situation, and this post is already frighteningly long so I am not going to even attempt to delve into it. But you do hear of these reunions every once in a while. And who knows – it’s probably happening a lot more than is ever publicized. With the Marvins, perhaps one thing that is kind of intriguing is that they were both from old New England Colonial families; Pamela even commented that “It’s quite possible that our families, the Downers and the Marvins, arrived on the same ship; they certainly arrived in the same year.” Maybe whatever link that may have developed through all those generations was just too deep not to exert some special sort of pull. It certainly is a charming story, and would have been even better had Lee Marvin lived longer. Still, as it seems he would have said himself, he had a pretty good run.

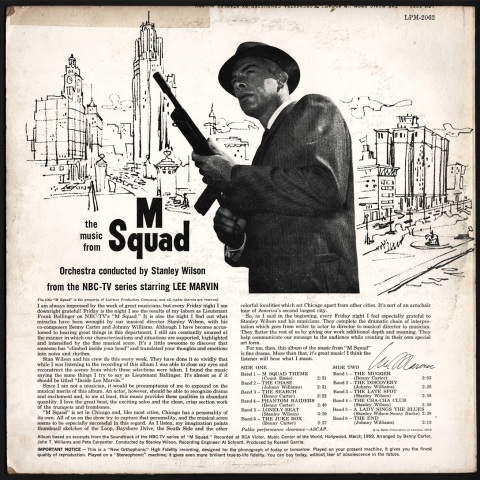

Liner notes by Lee Marvin (click to enlarge)