The American West, by Way of Ireland (and Scandinavia?)

September 29, 2010 § 1 Comment

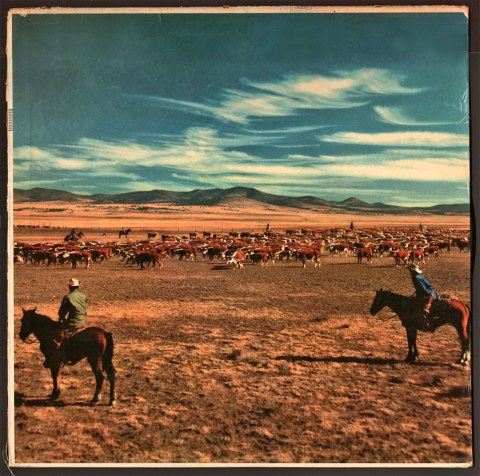

Ever since I happened upon a copy of this album several years ago, it has occupied a place in my mind next to the “Braff!” record of a couple of posts back, in that it was an immediate favorite as well as another example of a sleeve consisting of essentially an unadorned photo – though even more so in this case, as it dispenses with even the small album title and label logo found on “Braff!” I think it was again an inspired move, as the image certainly lends itself to an uncluttered presentation, and conveys the essence of the record’s content without much need for explanation: It would be hard to imagine a person turning the record over after seeing that photo and being surprised by its title, “Songs of the West.”

This album was released in 1955 – really not all that long after such a scene would have been something one would have still encountered on the American prairie – and consists of a collection of lush choral versions of classic cowboy songs by the Norman Luboff Choir. Luboff, born in Chicago in 1917, was a vocalist and arranger who came to Hollywood in the late ’40s to compose music for Warner Bros., eventually scoring over 80 films. In the mid-1950s he formed the Choir, and it went on to release over 75 albums of easy-listening material that, according to its iTunes biography, “drew on music from a variety of genres and geographic locales, with titles including Calypso Holiday, Broadway!, Songs of the Cowboy and Songs of the Carribean.” This was one of the group’s earliest, as well as most well-regarded, releases, and was a commercial success at the time. The choir also backed up vocalists such as Doris Day, Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, and continued to tour until Luboff’s death in 1987.

One feature this sleeve has that is so of that era is great liner notes, in which the tenor of the whole project is first described, and then each song is given a quick introduction. Thus it talks about the collection conveying “the mood and atmosphere of the great rolling lands of the American west,” and how these “songs and stories … excite the European imagination enormously.” In these “stretching spaces,” the back of the album continues, “men were few and lonesome, and their songs reflect this feeling. The imminence of death is there too, but there are also wild and wonderful nights in town.”

In reading the rest of the notes, though, one aspect that struck me was that two of the tracks are described as having probable Irish origins. Not that that’s a big part of the whole album, and certainly the link between Irish music and American roots (/folk/country/etc.) music is pretty well known, but it was something that got me thinking a little bit, partly, I suppose, as I had just seen the 2006 Oscar-winning (for best song) Irish indie film “Once” again the other night, and while watching it had remarked to my wife (who happens to be studying Ulysses at the moment) that it kind of reminded me of how when I lived in London I had discovered that so many English musicians actually have Irish roots. Many products of, especially, the northern cities of Liverpool (the “second capital of Ireland” as it is sometimes called) and Manchester have Irish backgrounds, including Paul McCartney (on both sides of his family) and, perhaps a little less known, John Lennon (who came from a long line of Irish singers on his father’s side, and named his second son with the Gaelic version of ‘John’; he also had Irish ancestors on his mother’s side, and one commentator has even called him “at least 65% Irish”). The genius partners Morrisey (surely one of the most literary pop lyricists ever) and Johnny Marr of the ’80s Manchester group The Smiths similarly share Irish roots; the term used to describe that sort of background is “Irish Mancunian,” which also applies to the Gallagher brothers of the best-selling ’90s indie band Oasis as well as Sean Ryder of Happy Mondays. Elvis Costello, whose mother was from Liverpool and whose songs were famously “wordy,” is another example of a British singer-songwriter with Irish antecedents. Even the Sex Pistols’ John Lydon qualifies, with a Gaelic-speaking father from Co. Galway.

Returning to Manchester, Mani, a bass player who ended up in two of the most seminal English bands of the last 25 years, the Stone Roses and, later, Primal Scream, even described himself as “an Irishman with an English accent,” which, the piece I came across continues, “is not unusual in Manchester, as one in three from the city claim to have some form of Irish roots.” (Apparently his and Johnny Marr’s family both came from the same rural part of Ireland and only immigrated to Manchester at the start of the 1960s. In an interview, Marr once related that “Years later, my mum said to me: ‘I heard that Nancy Farrell’s boy is in a pop group and doing really well” and I said ‘Who’s that?’ because I heard about the Farrells all the time, and she said: ‘It’s Gary, (Mani) the bass player. He’s in this group called The Stone Roses.’ I couldn’t believe this situation where a little farmland in Co. Kildare, Ireland, had the seeds of two musicians who were going to make it from the Manchester scene 30 years later.” http://forums.morrissey-solo.com/showthread.php?t=39401)

So reading about the origins of those couple of the tracks just kind of brought all that back to me, and made me once again appreciate the musical contributions of Ireland, and moreover just that of the whole of the British Isles – without which there would be … what, as far as pop music goes? It’s kind of hard to imagine.

A thought did occur to me, though, and I throw this out there realizing it may be pretty far-fetched. I don’t know whether it’s so completely off-base as to be crazy, or maybe on the other hand something people have speculated about, and I just am unaware of it; but anyway, just for the sake of following where it may lead… The Romans, who of course occupied England, never invaded Ireland, thus allowing the Celtic peoples (who arrived there some time between 600 and 400 B.C.) to develop their culture undisturbed. The one people who did manage to invade and intermingle their culture with the Gaels were the Vikings, who apparently had a presence there for about two hundred years starting in the 8th century. Interestingly, Dublin is actually a Viking city. If you want to trust Wikipedia here, it relates that:

“In 838, a small Viking fleet entered the River Liffey in eastern Ireland. The Vikings set up a base, which the Irish called a longphort. This longphort eventually became Dublin…The Vikings also established longphorts in Cork, Limerick, Waterford, and Wexford.”

I hope I will not offend anyone (I love Europe and in fact lived and studied in Belgium for several years, and speak enough French and Dutch to get by…) by saying that Europe does not – with a few exceptions here or there – have a reputation for producing much great pop or rock music. The one country that has always struck me as bucking this trend is Sweden (followed by, perhaps more prominently in recent years, Denmark). Beginning with at least Abba, that land of approximately 9 million people has turned out one group after another with a real flair for melodic pop songwriting. Even in the 1960s they had a knack for producing some of the finest non-English-speaking bands in the world – like, to take just one extremely obscure example, the Tages, who in 1966 released one of the world’s first psychedelic pop albums, and the next year even recorded at Abbey Road in London. I had never heard of them, but they were just one band I came across that only served to further my impression that Sweden has for a long time had a musical sensibility that most other European countries lack.

So again, this is perhaps reaching a little far, but if one thinks of much of Europe as eventually being under the Roman umbrella – and I have no idea exactly how related to the “Romans” Italians of today are, but let’s face it, that country especially, much as I also love it, has no tradition at all of quality pop music of the sort we are talking about here – perhaps the fact that Ireland never experienced that, and in contrast was actually influenced by Scandinavians, plays a small role in the fact that the Irish have had such a notable musical tradition? (And when I link Sweden in particular to pop music, I know that they were of course just one of the countries that produced Vikings, and in fact the Swedes tended to venture east into Russia, while Norway and Denmark spawned most of the Vikings who sailed to Ireland; but I’m not a Viking scholar or any kind of historian, and for the sake of argument I’m just going to think of Scandinavia as a whole as being a region that produced a people who intermingled with the Celts, and now is an area which, in at least a couple of places, seems to have a feel for that sort of music that is largely lacking in the rest of Europe.)

Now, who knows exactly what goes into being “good at” making pop music. And again, I am just kind of thinking out loud, but in pondering and reading about all this, a couple of further things struck me. One, it is pretty much a commonplace that Ireland, as well as being known as a very musical and literary nation, has a reputation for melancholy. “The Irish” states Mike Murray in an essay I came across entitled ‘Cannot Keep from Singing,’ “are a melancholy lot. No one who lives with us can doubt that.” He continues: “For all the famous — and infamous — cultural stereotypes involving our merriment (we hoist our glasses high and celebrate heartily when someone passes away, for crying out loud) we are nevertheless a people of deep cultural sorrow.” There is also a somewhat classic quote by the late United States Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who said, “I don’t think there’s any point in being Irish if you don’t know that the world is going to break your heart eventually.” There are doubtless hundreds more that could be cited, but the thing that struck me is that, for example, England has never really been seen in quite the same way, and neither have a lot of other northern European countries especially, but, coincidentally or not, both Sweden and Norway seem to be associated with a similar sensibility.

John Lennon and Yoko Ono singing about the “pain and the death and the glory, and the poets of old Ireland.” Dig that percussion.

I haven’t spent much time in either country, but I have had friends in Denmark since the 1980s and spent a fair amount of time there, and was always struck by what I felt was the difference between their more outgoing, happy-go-lucky sensibility and what one found across the water in Sweden. Not to over-generalize, but my experience seems to be reflected in some of the popular notions that Swedes tend to be on the “gloomy” side, or “serious,” “risk-averse” or simply “dull” – or even given to some sort of vague existential anxiety. In a book entitled Swedish Mentality I came across many references to the notion that Swedes are prone to a certain degree of melancholy – there is, strikingly, even a whole chapter called “Melancholy.” Whatever it ultimately is, or however it may express itself, is well beyond my scope here. One somewhat intriguing notion in the book that may be worth mentioning briefly, though, is that there are even theories that particular weather patterns can contribute to this phenomenon. It talks about how, in a 1981 Swedish book titled Weather-Related Illness and Airborne Ions, a Doctor Bertil Floistrup discusses atmospheric electricity and its effect on mood:

“He writes about the Atlantic low-pressure front, which begins to move toward Scandinavia at the latitude of the British Isles, and discusses how the positively charged small air ions … reach us 12 to 48 hours before the front and torment the sensitive with all manner of physical and psychic problems – what he calls ‘climatosis’ … Floistrup notes that life can feel meaningless and that stress symptoms can appear ‘like a cloud of anxiety, worry or apathy’.”

The book continues: “Low air pressure is not confined to the chillier climes, but Sweden is definitely one of the countries frequently subjected to it. For many, the consequences of this include, ‘migraines of a diffuse, protracted kind and a slight nausea. Psychic resistance is broken down, life seems hopeless, and one labors under feelings of meaningless and inferiority’.”

That sounds a bit dramatic, and of course there are all kinds of questions that then spring to mind. If that is at all a factor in producing some of the traits people associate with the Swedish personality, does that particular weather pattern not also effect Denmark, for example? There is certainly also the fact that a lot of the country is plagued by a lack of light a lot of the year, etc., etc. Again, it would take a lot more investigation and probably a variety of scientists to make a dent in some of those questions, but I’m just going to take it as food for thought, and move on to something else I discovered that had never quite struck me before, which is that in Norway they also have a reputation for both melancholy and – and this is what really surprised me – specifically a tradition of roots music that has been compared to both Irish and American country and western music. As a 1994 article from the music magazine “Listen to Norway” (found at mic.no) explains, “If you were to define Norwegian taste in one word, it would be ‘melancholic’… Roots dominates Norwegian popular music.” It continues:

“The origin of the collective Norwegian infatuation with C & W can be dated to spring 1964, when Nashville invaded Oslo and Jim Reeves … and Chet Atkins were on TV. The country was never the same again. It is true we ‘shook’ to the Beatles, but it was Jim Reeves who totally dominated the charts and the sole radio station. I Love You Because topped the charts for thirteen consecutive weeks, to be replaced by only one week of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night before [Reeves] crooned I Won’t Forget You from the number one spot for further nine weeks.”

That’s pretty revealing to me. And the article gets even more specific and talks about how “music theorists often point to the similarities between Ireland/Norway and the Midwest/Rocky Mountains,” saying, “It is no coincidence that roots music is currently strongest in Ireland and Norway.” It even points out how TV shows about the American West like Gunsmoke were inordinately popular in Norway in the 1970s. “A cowboy could not solve world problems. But he could relieve Norwegian melancholy.”

So it seems like there may be something in the sensibility of much of modern-day Scandinavia that intersects with Ireland and its music (and by extension American roots music and culture), which, if looked at against the background of this distant history, starts to seem intriguing. The 9th century is obviously a long time ago – but if you consider a generation to be maybe 25 years, it’s “only” 40-some generations ago, give or take a bit. I had contact with great-grandparents as a child; that’s going back three right there. In other words, maybe that era is not so long ago in some respects, and it isn’t so crazy to try to make sense of the development of cultural and artistic sensibilities against that kind of wide sweep. Does that mean that the Beatles or Smiths – or Hank Williams – are connected in some very faint way to some Vikings who set off in their ship looking for farmland and whatever else some 1200 years ago? I don’t know, but unless someone can poke a hole in all of this I don’t particularly see why it may not, and it’s actually kind of a nice thought. I do know that a group called the Concretes released a debut album in 2003 that is perhaps the most beautiful example of melancholy-infused pop music I have ever heard. They are from Stockholm. I also know that the Romans never invaded most of Scotland either (while it was by contrast a relatively easy trip for Viking ships, especially the northern islands; genetic testing shows that 60% of the Orkney Islands’ population today is of Norse ancestry), and that I have always felt that Glasgow has produced more inspired pop groups in the last 30 years or so than just about any other locale in the world. The quality and quantity coming out of that city of a little over a half million, especially once you take into account its size, is almost freakish. Maybe something in the amalgam of Scandinavian/Gaelic culture has been at work all these years in these areas? Something would have to account for it somehow.

In any case, this all just presented itself to me as at least something to ponder, prompted by my curiosity about Irish influence in so much of the music I happen to love. When I actually think about it, growing up I used to fall asleep to the radio as a very young kid, listening to what I consider real country music – the stuff made more or less from the ’70s on back. Then later I became engrossed in British pop/rock, to the point that I was the only person I knew of who listened to it to anywhere near that degree, and later I ended up moving to London and co-founding a band (known, perhaps not accidentally, for a sort of melancholy – or at least moody – feel to its music) there rather than in my native country. In some ways I still feel more at home there than I do here. Maybe that’s not all that surprising, though, as my background on my mother’s side is largely Scots-Irish?

When I return to the “Songs of the West” album, though, one of the songs noted as being of Irish origin is “Streets of Laredo.” It is thought to have originally been written as the Irish drover ballad “Bard of Armaugh,” and later was brought by settlers to Appalachia as “The Unfortunate Rake” or “A Handful of Laurel.” The current lyrics are usually attributed to a cowboy named Frank Maynard, who copyrighted them in 1879. It has supposedly been recorded by just about every folk or country artist since recording began, including Johnny Cash, and Arlo Guthrie called it the saddest song he had ever heard. Roger McGuinn of the Byrds (you can hear his version here, and follow the lyrics below if you wish as they are mixed a bit low on the recording) tells the story of how he first heard the song as a boy:

“The first time I heard this song, I was six years old, living in Tarrytown, New York. My parents had an old friend named Jack Morris who had just gotten remarried, and they were coming over for dinner that night. Jack’s new wife was pretty, with long black hair. She played guitar and sang. Her name was Ruby Norris-Morris. Ruby noticed that I was into cowboys from the way I was dressed and all the cowboy paraphernalia in my room. She asked if I’d like to hear a real cowboy song. ‘Yes,’ I said, not knowing quite what to expect. By the time she got to the second verse, a lump the size of an apple formed in my throat and I began to cry. It was such a beautiful melody and the story was so sad.”

Streets of Laredo

As I walked out on the streets of Laredo,

As I walked out in Laredo one day,

I spied a young cowboy all wrapped in white linen

Wrapped in white linen as cold as the clay.

‘I see by your outfit that you are a cowboy’

These words he did say as I boldly stepped by,

‘Come sit down beside me and hear my sad story,

I was shot in the breast and I know I must die.’

‘Get six jolly cowboys to carry my coffin,

Get six pretty maidens to sing me a love song

Take me to the graveyard and lay the sod o’er me

For I’m a poor cowboy and I know I’ve done wrong.’

‘It was once in the saddle I used to go dashing

Once in the saddle I used to go gay,

First down to the dram-house and then to the card house

Got shot in the breast, I am dying today.’

We beat the drum slowly and played the fife lowly,

And bitterly wept as we bore him along,

For we all loved our comrade, so brave, young and handsome,

We all loved our comrade although he’d done wrong.

To conclude, while I was thinking about all of this, and particularly about the deep feeling the Irish seem to have for music, one person in particular sprang to my mind – Jeff Buckley. I had never looked into it, but of course with that name he had to be of Irish extraction. (He is; his grandfather was descended from a school master in Cork.) My band had the good fortune to tour with him twice before he passed away in 1997, and he was a really nice guy, very sensitive (as demonstrated by how easily hurt he could get by some of what was said about him) and the creator of some of the greatest moments I ever witnessed in music. That would be whenever he performed the oft-covered Leonard Cohen song “Hallelujah” at each gig. The recorded version on Grace is unfortunately a pale shadow of any of the times I saw him do it live. Those renditions were so suffused with intensity and emotion it was truly incredible. I must have seen thousands upon thousands of songs performed by this point in my life, but almost nothing comes close to any of the times I heard him sing that, standing alone on stage with his guitar.

Buckley’s mother says that Jeff happened to be in Ireland the day his debut album was released: “For Jeff to be in Ireland on the day that Grace was released was just, in a very strange way, very prophetic I think. There couldn’t have been a more significant place for him to be, truly. The ancestral eyes were upon him truly. What a lovely thing.”

I have a few stories connected with him, but I don’t think this is exactly the place to relate them right now, and this post is already incredibly long as it is. I have always found it strange, though, given his untimely and tragic death, that of all the people we toured with, including Radiohead, he was the only one whose autograph I ever requested. And he didn’t just scrawl his name, but drew a picture and wrote something about what had happened that day in addition to signing it. He was clearly pained by a piece that had just come out in the music weekly New Musical Express that had said something about him he found hurtful. I don’t think it was ultimately too unflattering, but he had taken it that way.

And in light of all this reflection about the Irish character, I suppose it is no accident that when Buckley surprisingly decided to cover a song by my band, he chose what has to be the saddest one, “Alive” (from the 1995 debut album, Drugstore). Between playing it and just listening to it I have heard it hundreds if not thousands of times, so I suppose it has lost some of its impact for me, but hearing him sing it (there is a lo-fi live recording from a gig at the end of 1995) brings it back quite a bit; at points it is actually kind of hard for me to listen to, especially given what would happen to him not too long afterward. He was a unique and obviously incredibly talented guy, with a certain open, real, poetic spirit that came across strongly. He was also quite funny. I didn’t know him very well at all, but kind of miss him all the same.

“Oh this is perfect.” Jeff Buckley performing “Alive” solo in 1995